ATMA and CEPT University

With being conscious of the importance of the architectural heritage that it is in possession of, ATMA has joined hands with CEPT University. CEPT University is a premier institute in the country for understanding, educating, designing, planning, constructing, and managing human habitats. Together, the two institutions seek to revitalize the building as a design, architectural, cultural, literary nerve of the city. Along with this, CEPT also brings its domain of expertise and goodwill in the field of architecture and the built environment, and hence helps ATMA in the day-to-day functioning, planning, curating, and managing of the premise along with establishing methods and systems to care for the building in the long term.

The facility is now available for a diverse range of events, encompassing architecture, design, literature, academics, culture, and industry gatherings.

Ahmedabad Textile Mills Association

A Brief History of the Textile Industry in Ahmedabad (1859-1980s)

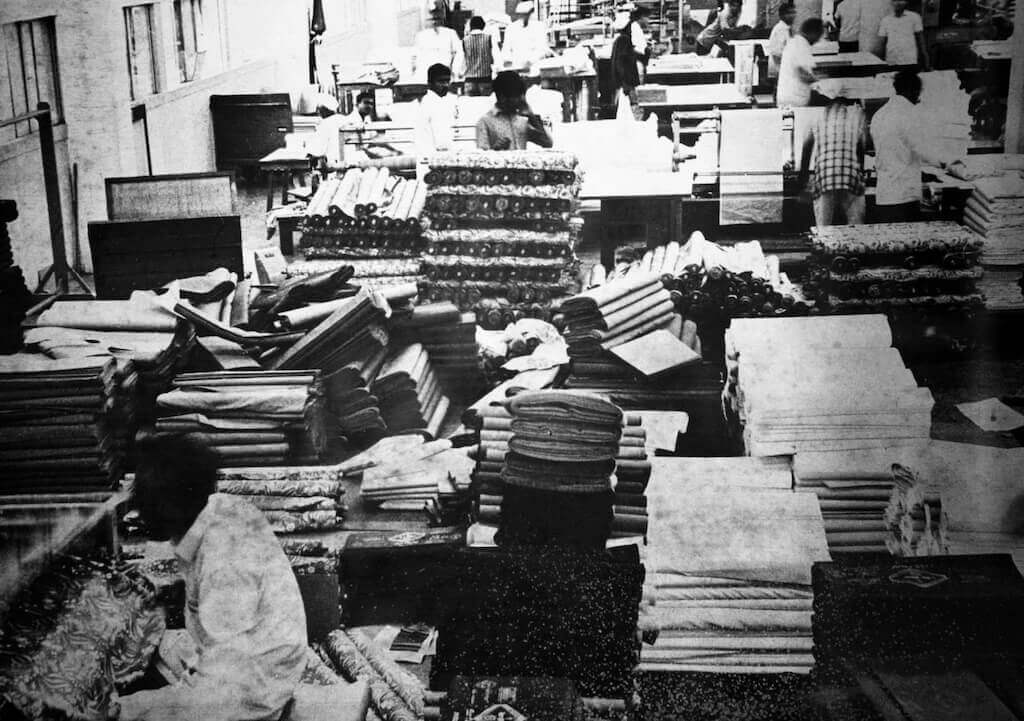

The origins of the Textile Mills Industry in Ahmedabad can be traced back to pre-independence India when the city and much of the country was under British rule. During this period, Ahmedabad experienced a remarkable growth in population, trade, and a resurgence in traditional cotton, silk, and gold production. Capitalizing on this favourable environment, Ranchhodlal Chhotalal laid the foundation of Ahmedabad's first textile plant in 1859, a time when Gujarat was still a part of the Bombay Presidency. Despite initial setbacks due to a mishap in the delivery of ordered machinery from England, Chhotalal's unyielding spirit prevailed, leading to the establishment of the first mill in Ahmedabad.

Despite the prevailing unfavourable conditions that were inherent to the city; such as the city's dry and arid climate, limited port facilities, lack of a railway network, and the modest quality of local cotton, the availability of local financial capital along with an entrepreneurial spirit, played a decisive role in setting up mills in Ahmedabad. In 1891, by which time a few other mills were established, Ranchhodlal Chhotalal further championed the cause by founding the Ahmedabad Millowners Association, aimed at safeguarding employee interests. The city's economic progress received an additional boost following World War I, as the cessation of British empire imports provided Ahmedabad's mills with the opportunity to better cater to India's requirements.

By the time Gujarat attained independence in 1960, Ahmedabad boasted an impressive tally of over 80 to 90 mills, earning it the moniker "Manchester of India." Alongside the flourishing textile industry, the influence of wealthy capitalists left an indelible mark on Ahmedabad's modern architecture. These industrialists, who ranked among the city's wealthiest individuals, channelled their affluence and influence into supporting the establishment of educational institutions, scientific research endeavours, and cultural promotion initiatives. They were amongst the country’s biggest institution builders that changed the city of Ahmedabad forever. The collective spirit of emerging independence, the magnanimity of textile wealth, and the principles of self-reliance and community collaboration converged during what architect B.V Doshi aptly dubs "The Golden Age" spanning the 1950s to the 1970s.

The MillOwner’s Building

A Testament to Le Corbusier's Vision (1951-1956)

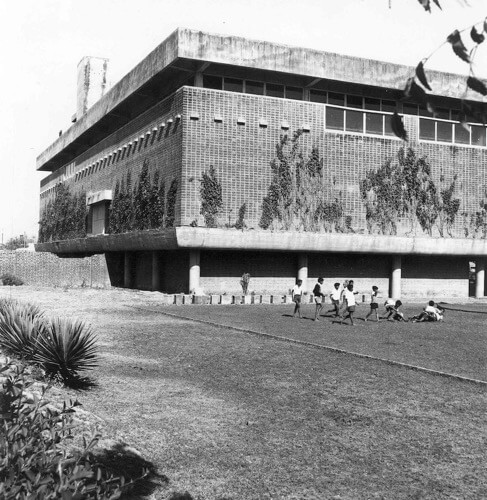

The MillOwner’s Building holds a momentous place in Ahmedabad's rich heritage of modern architecture as it seamlessly bridges the city's textile industry with modern architecture of the world. When tasked with designing the headquarters, Le Corbusier perceived it as an opportunity to harmoniously blend his distinctive architectural language, drawing inspiration from a villa, with the essence of traditional Indian architecture. The resultant synthesis is beautifully showcased in the building and is also observed in the Millowners’ stance on life that was deeply rooted in culture and religion along with a strong capitalist outlook that could use industrialization to its advantage.

The construction of this building took approximately four years, yet the journey was not without its challenges. Conflicting visions between Le Corbusier's ideal of a post-capitalist India and the millowners' capitalist perspectives sparked overt disputes. Contentious discussions ensued, encompassing matters such as fees, door widths, and profound debates on materials. As financial tensions escalated, direct communication between Le Corbusier and the client ceased, ultimately paving the way for a more prominent role for Doshi in the project. A young Doshi was working at the time in Corbusier’s Paris office and was stationed in Ahmedabad to oversee and complete this project.

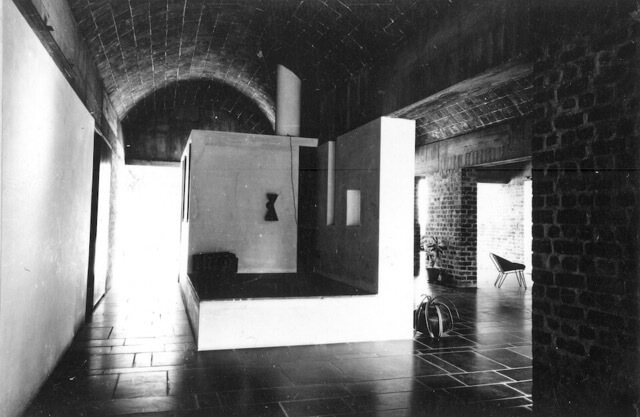

The clash over financial matters became so acrimonious that Le Corbusier refrained from communicating directly with his client for several months. This circumstance provided the opportunity for Doshi to assume a more substantial involvement. The construction process exemplifies Le Corbusier's astute utilization of local technological conditions, harnessing their full potential. Notably, this project stands as one of his later works, characterized by the application of refined iterations of his conceptual ideas. It is undeniably a profoundly poetic space that is made evident by a beautiful fusion of different architectural elements, a masterful understanding of volume, and the best possible use of juxtaposition in architecture - orthogonality vs curvilinearity, private vs personal spaces, open vs closed spaces, modern vs traditional and more.

Concept

The architectural design for the headquarters was conceived to cater to the diverse business, social, and cultural activities of the association, encapsulating its dual nature of being both public and private. The terms "little palace" and "display" to describe the building which is quite unique and timeless.

Context

Located between the Sabarmati River on one side and Ashram Road on the other, the building acts as a spatial interface, with one facade facing the urban context while the other embraces the surrounding landscape. Le Corbusier responded to Ahmedabad's dry and arid climate by responding to the harsh sunlight and by creating strategies that enabled ventilation. Employing the "brise-soleil," or sun-breakers, along the western façade that faces the road and fins on the eastern façade facing the river, coupled with strategically placed vegetation, the building achieved optimal ventilation throughout the year. Conversely, the stone-clad south and north façades remain relatively unadorned, punctuated by only a few openings.

Circulation

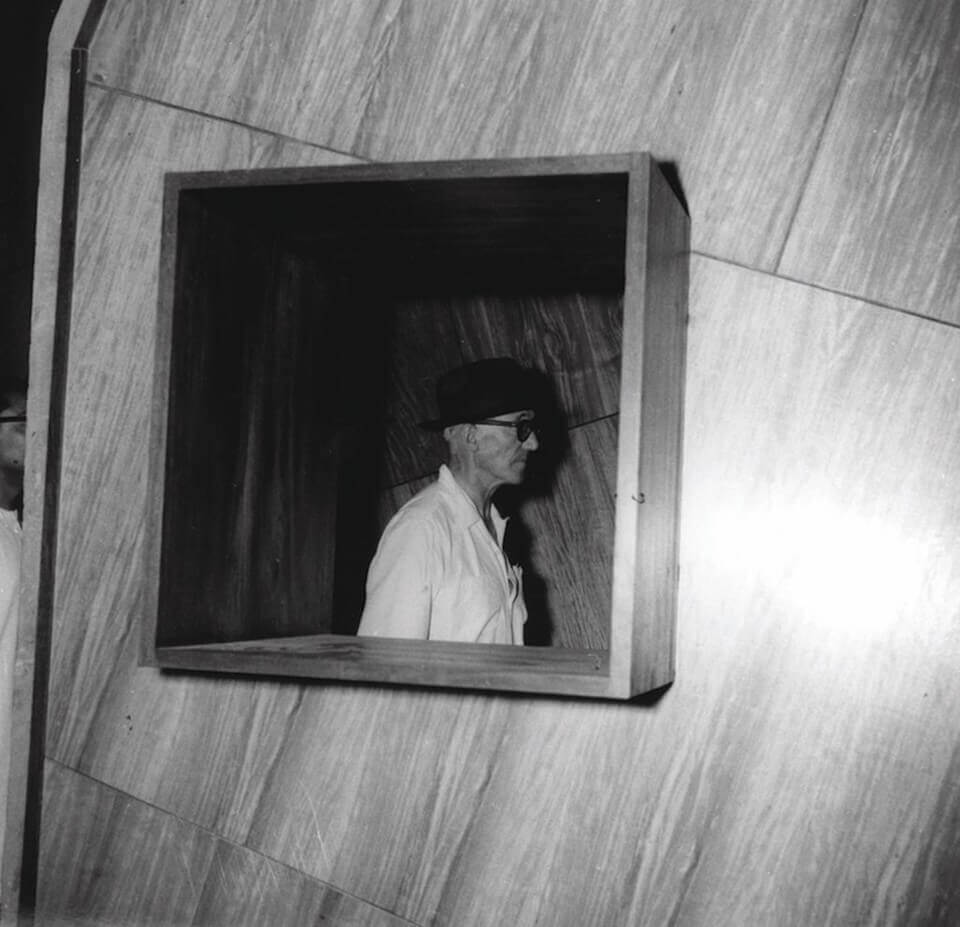

Le Corbusier introduced two distinct modes of circulation, reminiscent of his residential architectural designs. A ceremonial ramp offers a direct ascent, culminating in a two-story blind wall featuring a singular square window, serving a security purpose and framing a panoramic view of the river landscape from the first-floor lobby. Adjacent to the ramp, a separate stairway completes this architectural promenade. Drawing parallels to his design approach in Villa Savoye, where ramps facilitated resident and guest movement while staircases catered to servant circulation.

Program

Echoing the design philosophy of Villa Cook, Le Corbusier sought to segregate public and private spaces, manifesting his vision of a "home as a palace." Acquainted with the millowners' association's organizational and managerial practices, he arranged the administration offices, presidential chamber, conference room, and seminar room on the first level. Complementing this arrangement is a semi-open area affording a framed view of the river. Meanwhile, the ground floor, second floor, and terrace were intended for public gatherings.

Structure

Within the nearly square design, an orthogonal structural grid contrasts with curving walls, horizontal slabs, and diagonal planes. The presence of a picturesque circulation is distinctly delineated along an ordered path. The project adheres to a grid layout comprising 12 modules, aligned with three modules in the east-west direction and four modules in the north-south direction.

Light

The interplay of geometrical elements, the rhythmic opening and closing of apertures created by distinct façade frames along the eastern and western sides, and the gradual tapering of lower fins on the western façade contribute to the visual drama and manipulation of light and shadow within the space.

Le Corbusier

The Maestro of Architecture

Renowned as an architectural acrobat, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, widely known as Le Corbusier, left an indelible mark in the world of art and architecture. A Swiss-French architect, furniture designer, urbanist, writer, theoretician, sculptor, and painter, he was a pioneer in the development of Modern architecture. Over the span of his illustrious five-decade career, Le Corbusier erected structures across Central Europe, India, Russia, and North and South America.

During his formative years, he embarked on extensive travels throughout Europe, diligently studying architecture and meticulously documenting his observations in countless sketchbooks. Le Corbusier's restless wanderings fostered a rich understanding of diverse architectural styles and influences. Notably, he devised a measuring system known as the "Modulor," which he employed to place humanity at the heart of architectural and design endeavours. Rooted in the principles of the golden ratio and human proportions, this distinctive silhouette found expression not only in his architectural creations but also in his paintings.

Throughout his architectural oeuvre, Le Corbusier developed a cohesive set of design principles that encompassed pilotis (supporting pillars), roof gardens, open floor plans, expansive windows, and detached facades. He consistently emphasized the paramount importance of considering people as a collective entity, and his visionary urbanist perspective has since become a guiding principle in modern urban planning.

Le Corbusier in Ahmedabad

"Urbanism is the activity of society. Capital is the spirit of a nation."

In 1951, Le Corbusier received the prestigious commission to develop a plan for Chandigarh, a defining moment for India as it emerged from a hard-fought struggle for independence and sought to establish its identity and place among the ranks of developed nations. Who better to design a Modern capital than the most famous Modernist Architect in the world?

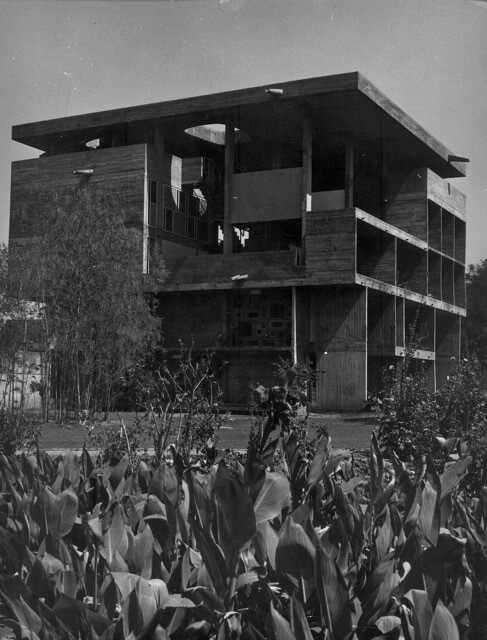

It was during this transformative period that Le Corbusier was invited to Ahmedabad by Surottam Hutheesingh, the president of the Millowner's Association, and Chinubhai Chimanbhai. Their collaboration resulted in the construction of the association's headquarters, three millowners' residences (only two of them built), and a city museum. Despite being constructed within the same timeframe, these structures display a remarkable diversity and contrast in terms of form and materials employed. Corbusier has designed 4 buildings in Ahmedabad.

During his initial visit to Ahmedabad, Chinubhai Chimanbhai entrusted Le Corbusier with two projects: a city museum and a personal residence. While the villa for Chinubhai Chimanbhai remained unbuilt, Le Corbusier was granted the opportunity to construct the museum, drawing upon concepts he had been exploring since 1929. In the spring of 1951, Surottam Hutheesingh commissioned Le Corbusier to design a house that would reflect the lifestyle of an affluent bachelor ready to enter into marriage, necessitating a variety of spaces and an impressive entrance. Subsequently, Surottam Hutheesingh sold the design to fellow millowner Shyamubhai Shodhan.

Le Corbusier astutely considered Ahmedabad's climate, culture, and the inherent contradictions of a population with a modern outlook yet deeply rooted in tradition. One distinct feature of Corbusier's architectural philosophy, evident across his projects in Ahmedabad, is his emphasis on rooftops as valuable spaces rather than mere wastelands. Examples include vegetable farming in Villa Sarabhai, hydroponic cultivation planned for the Sankar Kendra roof, and the utilization of terraces as outdoor spaces in the MillOwner’s Building.